Presence, Power, Persistence

Twenty-first century museums increasingly are assuming a new role: as change agents. They use social capital and authority to engage with the public on social issues. They encourage visitors to question and challenge their established values. Collections, exhibits, and programming become vehicles to improve the lives of the people in their communities. Discussion and engagement as a mission-driven activity flows from an evolving point of view of museums’ obligations to the people and communities around them. In taking on these tasks, they redefine their public value.

While museums’ obligations to be of public value are not new, activism is. The American Alliance of Museum’s (AAM) broached the topic by selecting Gateways for Understanding: Diversity, Equity, Accessibility, and Inclusion in Museums as the 2017 annual meeting’s theme. They asked the question: “How do we strengthen our museums’ roles as safe environments for cross-cultural dialogue and interactions?” In selecting the theme, AAM challenged museums to embrace activism as a critical function. According to AAM, today’s museums not only have the possibility of activism but more importantly own it is a critical role. Museums are encouraged to become public advocates and community anchors.

However, becoming agents of social change comes with a mixture of risk and reward. In a politically polarized climate, taking a stand on contentious issues may be risky. Activism removes the long-cultivated cloak of objectivity. It challenges the historic perspective of what a museum should be.

The evolving role of museums in public discourse

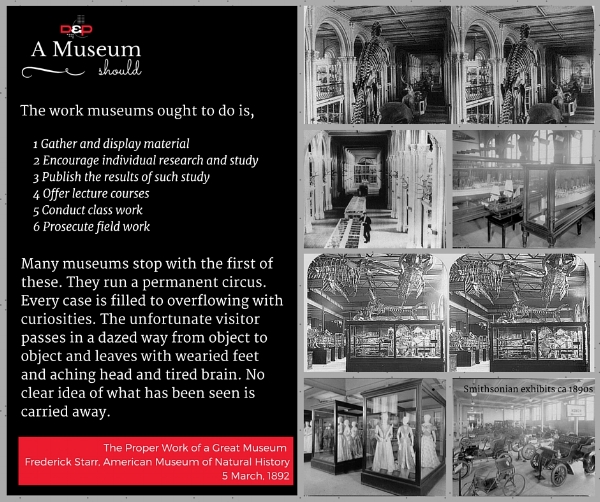

The nineteenth-century vision for a museum was as a repository for artistic masterworks and artifacts of great historic significance. By the end of the century, the role of the museum expanded to include research institution. Significance was conferred by a provenance associated with great men, and educated elites made up the majority of visitors. Collecting choices self-reinforced the notion that museums housed culturally elite artifacts and works for the benefit the culturally elite.

Changes in American society, including an immigration surge and social upheaval with the rise of “new money” industrialists, provoked a conservative, cultural retrenchment. Though art museums often demonstrated preference for European work, history collections promoted American exceptionalism. Both choices expressed clear cultural values. Beginning in the Gilded Age, museums offered educational programming that explained and defended those values to an expanding middle class as well as new money philanthropists.

In 1892 Frederick Starr of the American Museum of Natural History declared that “[i]n the display, the fundamental idea should be the instruction and profit of the visitor.”

However, a new round of social changes in the mid-20th century challenged museums to rethink collections and education practices. The new social history scholarship into the lives of underrepresented groups influenced these choices. Museums incorporated social history themes into exhibits to reflect contemporary culture and presumably patrons’ interests. Thus began a slow re-assessment of the stories, artifacts, and themes deemed worthy of museum exhibition.

African American museums led the way in museums becoming more democratic and personal

Prior to the 1960s, few museums collected cultural artifacts from ordinary people. African American museums were notable exceptions. Before 1950, about thirty historically black colleges, universities, and libraries operated museums. They preserved African American cultural heritage while celebrating their accomplishments and contributions. As the Civil Rights Movement progressed, new museums opened as stand-alone non-profits. They included the African American Museum in Cleveland (1956), the DuSable Museum of African American History in Chicago (1961), and the International Afro American Museum in Detroit (1965). The rhetoric of the Civil Rights Movement placed the struggle for equality and freedom in a long historic context of oppression and disenfranchisement that was supported by the new scholarship and museum programs.

Within a generation of the Civil Rights Movement’s significant events, people founded museums to commemorate them. New museums, such as the National Civil Rights Museum, interpreted events from within living memory. Moreover, in interpreting non-elite culture, they created a role for museums to support communities. A network of activist museums grew that questioned elite, cultural hegemony. They challenged traditional museums to include traditionally disenfranchised groups among both collections and audiences.

Over time, the wider museum field responded by adopting more inclusive practices and expanding collections. They created outreach programs to encourage visitation from among broader demographics. In response, visitors expressed their needs for relevant experiences that reflected their attitudes, beliefs, and culture. Diversity initiatives spring from a more inclusive vision of America that recognizes and celebrates equality. Social activism on behalf of inclusion is a natural progression.

What do modern audiences think of museum activism?

Not surprisingly, audiences are not agreed on museums as social activists.

Know Your Own Bone used data from the National Awareness, Attitudes, and Usage Study to conclude that the general public views museums as highly credible sources of information. The public ranked museums, zoos, aquariums, and science centers above government agencies, non-governmental organizations, and newspaper for trustworthiness. The same survey reported that many Americans believe that museum should suggest or recommend actions for the public to take to support causes and missions. That perspective is more prevalent, though not a majority, among younger visitors.

A MuseumNext survey found that many Americans are unsure whether museums should “have something to say on social issues”. While the source of ambivalence isn’t clear, the study pointed out that more frequent museum goers were more likely to say that museums should express opinions about social issues than non-museums goers as were younger visitors. The survey also found no majority among any group for wanting to visit an activist museum or for that same museum being “more relevant” to them.

Next steps towards effecting change

Becoming a change agent represents both risk and reward for 21st-century museums. Taking a stand on or advocating for social issues is a natural progression from the democratization of museum over the 20th century. As museums face their individual decisions and assess their audiences’ appetites for adopting changing roles, they can look to successful models within the field.

African American museums led the contemporary transitions of museum from repository of elite culture to 21st-century community anchor. The African American Association of Museum’s 2017 conference theme identified the understanding of social movements, including Civil Rights, Black Power, and Black Studies, that fostered 1960’s racial consciousness and cultivated the creation of Black Museums. The conference challenged museums to embrace the role of social activism while developing sustainable models for furthering the same. The example of African American museums as community anchors makes a strong case for museums taking on the challenge as they expand their audience outreach.

D&P is proud to be a lifetime member of the African American Association of Museums and a sponsor of the 2017 conference.